By Travis Douthit/photos as noted

By Travis Douthit/photos as noted

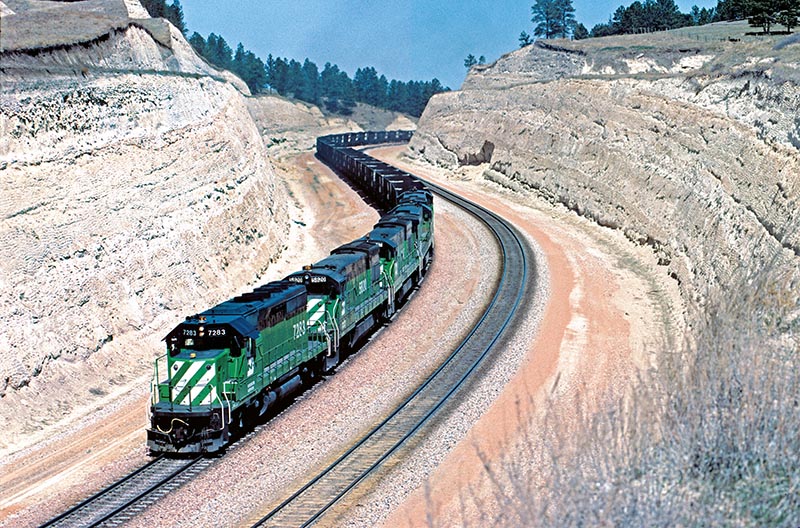

During the 1970s, the tiny community of Belmont, tucked away off State Highway 71 in northwest Nebraska, experienced a fairly quiet existence. Belmont, at 4,496 feet, is one of the highest points in Nebraska. Located on Burlington Northern’s former Chicago, Burlington & Quincy route that ran between Alliance, Neb., and Huntley, Mont., the town witnessed the passage of Laurel, Montana–Kansas City, Missouri Time Freight Nos. 74 and 75. Because of the sparse traffic, not many rail enthusiasts paid much attention to Belmont.

Belmont’s claim to fame was the existence of the only railroad tunnel in Nebraska, which sat at the top of a 1.55 percent grade known as Crawford Hill. The distance between Crawford and Belmont on BN’s Alliance Division, 2nd Subdivision is only 13 miles. Trains had to navigate two sharp 10-degree double horseshoe curves for the railroad track to gain 800 feet in elevation. If that wasn’t grueling enough, the railroad laid the track here with jointed rail and minimal ballast, contributing to the difficult nature of running trains over this route.

For the most part, Time Freight Nos. 74 and 75 experienced little trouble in navigating this secondary route regularly, since train lengths were short, tonnage was low, and traffic was sparse.

As the 1970s fast approached, the landscape on Crawford Hill would soon be altered, disrupting the solitude of a few hearty souls who called Belmont home. AMAX coal, a New York-based giant coal mining company, met with Burlington Northern operating officials to build a proposed 14-mile spur south from BN’s line at Donkey Creek, Wyoming (east of Gillette, Wyo.) to access the company’s proposed open pit coal mine at Belle Ayr in Wyoming’s Powder River Basin. Operations at the Belle Ayr mine officially began in 1972. The mine started shipping coal the following year, having secured a contract with the Public Service Company of Colorado and its newly constructed Comanche Power Plant in Pueblo. Naturally, these unit coal trains headed north toward the connection at Donkey Creek before turning east and straight for Crawford Hill.

In the early 1980s, Belmont, Neb., could be a busy place. Oftentimes, multiple helper sets converged at Belmont, before the BN dispatcher could line them back down the hill to Crawford. This was the case on a hot July afternoon in 1981. After helping a pair of unit coal loads, the BN Dispatcher has given permission for the combined pair of three-unit helper sets comprised solely of SD40-2s to finally head back down the hill and return to Crawford. In less than a minute, BN No. 7138 will enter Belmont Tunnel. —Travis Douthit photo

AMAX’s initial interest in mining the Powder River Basin stemmed from the U.S. Government’s Clean Air Act of 1970 crafted to control air pollution and regulate air emissions from stationary and mobile sources. The Powder River Basin’s cleaner-burning, sub-bituminous coal opened the floodgate for other coal companies to enter the region, including the areas in northeastern Wyoming and southern Montana.

As the number of coal mining companies increased, so did the requests for rail service. BN filed a petition with the Interstate Commerce Commission in October 1972 to build a 116-mile line from the south end of the new Belle Ayr mine spur to Orin, Wyo. The east switch of Orin Junction was located a few hundred yards northeast of Bridger Junction, Wyo., on BN’s former CB&Q route that ran between Wendover and Casper.

The Pine Ridge country of northwestern Nebraska did not immediately feel the ripple effect of the Powder River Basin’s economic boom. A few extra coal trains did not create too much havoc on this single-track route. However, by the mid- 1970s, BN operating officials realized the railroad needed to do something soon to handle increasing coal traffic over the route. Crawford Hill quickly became an operational bottleneck with the influx of Powder River Basin coal trains headed east toward Denver, Colo., or Lincoln, Neb.

A three-unit helper set has dropped the caboose on the fly, and the rear end brakeman works the brake wheel to slow its approach to the waiting coal train. — A.J. Wolff photo

Three-unit helper sets of locomotives were stationed in Crawford. Heavy 12,000 to 14,000-ton unit coal trains had to stop at Crawford, cut off the caboose, add the helpers, and then tie on the caboose behind the helpers. After a quick air test, the heavy train began to climb Crawford Hill heading toward Belmont. At Belmont, the helpers uncoupled from the train and returned light to Crawford. BN staged up to three to four helper sets, typically EMD SD40-2s, at Crawford. Fuel tenders, rebuilt tank cars equipped with m.u. cables and air lines, kept the helpers on the ready. The fuel tenders allowed the helper sets to remain somewhat captive to this remote area. The dance of adding and cutting off helpers played out regularly throughout the late 1970s. Even with Crawford Hill’s limits and the constant threat of derailments, BN operating personnel managed to make it work.

In February 1981, BN embarked on a massive re-engineering project to eliminate tight curvatures, add a second main line track, and daylight the only tunnel in Nebraska. Burlington Northern spared no expense in transforming the existing right-of-way into a state-of-the-art railroad line. The route acted as a conduit for Powder River Basin unit coal trains and provided a fluid and efficient transportation network to handle the increased coal traffic.

I was fortunate to experience Crawford Hill before the massive engineering project. I was a young 8-year-old with a small Kodak Instamatic camera using 110 color slide film when my father and I tagged along with our dear friend A.J. “Jack” Wolff. We spent a cloudy afternoon in early March 1978 at Belmont. Jack had made a trip to Crawford Hill in July 1977, and after hearing about his trip, it piqued our interest. That March trip was an eye-opener for Dad and I. We quickly planned another trip with Jack the following summer with the hope of better weather…